The ‘dual control mechanism’ as part of the glucostatic theory.

Eating behaviour is regulated by:

–fat stores (lipostatic hypothesis) and

–glucose levels (glucostatic hypothesis)

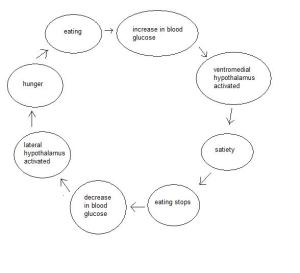

The ‘Dual-Centre Theory’ is made up of 2 parts: the ventromedial hypothalamus (VMH) and the lateral hypothalamus (LH). The VMH is like the ‘satiety centre‘ which means this is where fullness is detected and therefore tells the body to stop eating. When the glucose levels are increased, i.e. after eating, then the VMH is activated, achieving satiation (the feeling of being full.) When the eating has been stopped for too long, and the blood glucose levels have dropped, the LH (the ‘hunger centre‘) detects this change and is activated. This makes the body feel hungry, and ghrelin is produced. This is a hormone, and is the familiar rumbling sound stomachs make when an individual is hungry, and is basically the body wanting glucose levels to be increased, and this is achieved by eating.

Every individual has a set point, and their weight is regulated by the set point which is determined by the hypothalamus. The body will maintain this weight as it is practiacally ‘programmed’ into the body.

Karl Lashley was one of the first psychologists to suggest eating behaviour is linked to the brain and isn’t just a reflex.

He used rats to support his growing belief that neural mechanisms are involved in decision making. He cut out different areas of the brain to see the effect on their ability to negotiate a maze successfully and reach the food placed at the exit as a reward. Rats who VMH has been lesioned developed overeating and obesity.

He discovered how vital the role of the hypothalamus is in playing a part in the regulating of food intake. In particular, the LH was identified as the main hunger centre and the VMH as the main satiety centre.

Evidence for the Dual Process

Research from the 1940’s onwards has been done on animals. It has shown that lesioning areas of the LH in rats, dogs and other animals led to a loss of interest in food and eating, and the animals seemed to be unaware of the fact they were denying their bodies food, therefore starving themselves.

However, Gold (1973) found that lesions restricted to the VMH alone did not result in hyperphagia (overeating) and only produced overeating when they included other areas such as the parvoventricular nucleus.

Evaluation

– These studies are dated, and therefore may not be relevant or contain useful up to date information.

– We can’t generalise for rats to humans. Having different brain structure may mean different things would happen to rats and other mammals than would to human beings.

+ They contain good empirical evidence, therefore isn’t based on just theory.

+ They are still influential and still relate to and support other studies.

The role of leptin (lipostatic theory) in eating behaviour.

Leptin is a hormone, and acts upon various hypothalamic areas and seems to inhibit the release of another neurochemical called neuropeptide Y (NPY) This is the neurotransmitter stimulating hunger and eating behaviour.

Leptin is secreted -> hypothalamus is signalled: calories are high enough -> body ceases to release fat cells -> hypothalamus detects this drop therefore equalling the feeling of hunger.

Ravussin et al (1997) conducted a longitudinal study and investigated the Pima Indians, a population prone to obesity.

Two weight-matched groups were studied over 3 years and it was found that mean plasma leptin concentrations were lower in the group that gained weight than in the group that did not